Reef Creature ID: Tropical Pacific special limited edition available

Many underwater photographers will be familiar with the New World Publications guides to marine life and, available in a special limited edition today, the authors have produced their most ambitious guide yet: Reef Creature Identification: Tropical Pacific. It identifies some 1600 marine creatures, with over 2000 photographs and covers the geographic area from Tahiti to Thailand. Included in its 500 pages are photographs documenting both new species, and the ground-breaking taxonomic research of 40 scientist specialists. Reef Creature Identification: Tropical Pacific is available as a special signed and numbered pre-release edition from today, either as one of the first five books which are available for auction with the proceeds going to the charity REEF or as special signed and numbered editions (books 6-500). The book will be on general release from late October in the Far East, and November in the US.

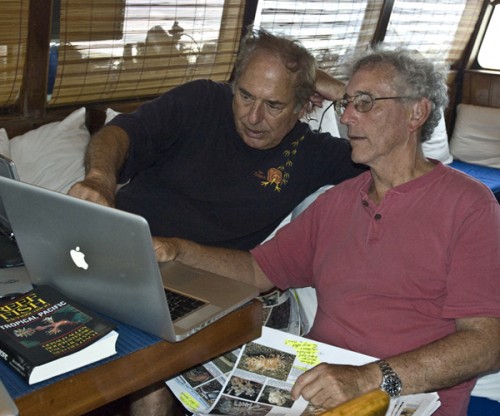

As a part of this pre-release, Wetpixel were able to track down the authors, Paul Humann and Ned Deloach, and they granted us an exclusive interview about the new book and the techniques they used during its five-year production:

What compelled you to tackle such a Herculean Task?

Paul: In many respects it just seemed like a natural step after the publication of the Reef Fish Identification Tropical Pacific in 2004. Nonetheless, I resisted the idea for quite a while because of the sheer number of invertebrate species involved, which, among other considerations, created the problem of keeping the book to a functional size, yet still remaining comprehensive. Finally we decided to limit the content to mobile invertebrates; primarily crustaceans, mollusks, worms and echinoderms, and we were off to the races. As it turned out, the race lasted five years, and the book still came in at a hefty 500 pages.

Glancing through the pages, what struck me besides the quantity of images was their quality.

Ned: Paul and I worked hard at both taking and selecting the images. In many cases a portrait in our book will represent a particular species to the public for years to come. Because of this, we feel compelled to present an animal in its best light. We also had some first-rate help. More than 60 photographers contributed to the project; many of them are among the best critter shooters in the business.

What are the criteria for a good identification photograph?

Paul: Basically a good image should be pleasing to the eye, clearly show a species’ distinctive features, and be taken in the animal’s natural habitat.

How comprehensive is the book?

Ned: It is by far the most complete field guide compiled for the region, but the natural history of marine life is so poorly documented, that our work, though significant, is only the most recent step in a continuing process. I find it exciting to think about how many great animals are still out there waiting to be discovered. Digital photography is an impressive new tool for documenting marine wildlife of all types. Even though an unknown animal can’t be given species status from a photograph alone, an image establishes that a new species exists and indicates where it might be found.

How were you able to get such a large inventory of photographs identified?

Paul: After organizing our library of images into broad classifications we made as many identifications as we could from popular and scientific literature. Then we began contacting specialists around the world who often referred us to other specialists. By the time we finished, 44 scientists had put in a significant amount of time and insight into the project, which we greatly appreciate. The identification process is not as simple as one would think. Marine taxonomists are traditionally more interested in the arrangements of mouthparts or the number, size and location of spines for instance rather than what a species looks like.

Looking through the galleys, I noticed quite a few animals designated as Undescribed or Undetermined?

Paul: The listing of “Undescribed” is, for the most part, a historical problem related to access to marine animals before scuba. For hundreds of years, the most practical method for acquiring marine specimens was dredging the bottom and dumping the contents on deck. Scientists would sort through the mess pulling out interesting specimens that were preserved in jars to be examined and described at a later date. As you can imagine, many elusive or cryptic animals were easily missed. This coupled with a backlog of taxonomic work due to the great numbers of marine animals coupled with a perpetual shortage of funding has left many species unstudied and still undescribed.

Those species designated as “Undetermined” are an artifact of the traditional descriptive method. By the time the preserved specimens were examined most had lost their natural colors and markings. Often, those characteristics essential for visually identifying a living specimen are absent from scientific literature. If a scientist felt that a photographed animal had been previously described, but was unable to compare its diagnostic features, because of its small size or obscure nature, the species was listed as undetermined. The best way to ameliorate this problem requires photographing an animal then collecting the same specimen for direct comparison with the literature. Fortunately, this is something that many taxonomists are interested in pursuing.

I was pleasantly surprised to see the behavior section. Is that something new?

Ned: My wife Anna and I had previously spent considerable time studying the behavior of fishes, for our book Reef Fish Behavior, but this is the first time we had an opportunity to focus on invertebrates. We quickly became fascinated with their nature, especially the cephalopods, and felt our observations would make a nice addendum to the book.

What was the most enjoyable part of the project?

Ned: The hunt! When you are searching for 1,600 different animals you have to be willing to look everywhere. And that is what we’ve done for the past five years. We scoured reefs, walls, sand flats, rubble fields, grass meadows, surge zones, algae beds, regularly poked around dock pilings and even under coastal out houses. In the process, I must have turned over a million rocks! It was like a five-year Easter egg hunt, with plenty of well-hidden treasures to discover.

We also enjoyed our association with Indonesian dive guides who turned out to be the project’s biggest asset. The large number animals in the book is directly due to their hunting skill and hard work. I have to make special mention of Liberty Tukunang from Kungkungan Bay Resort in Lembeh, who acted as our regular guide for the last four years. He could not only find the most cryptic species, but he also knew what we had already had in the can, and what we were still looking for. Unless we were on a particular mission, I let Liberty’s instincts dictate a dive. Often, I wouldn’t see him for an hour or so. When he finally returned he invariably had found a crackerjack animal to take me back to.

Do you have any idea how many dives you have made capturing the images for the book?

Ned: We don’t count dives, but typically we are underwater five hours a day every day of the week, and frequently at night I might add. Many species, especially crustaceans, only come out after dark. Every evening we had access to our own boat, we would be in the water from sunset until eleven, just in time for Liberty to catch the last bus home. I’ve never night dived so much in my life, and loved every minute.

I understand both of you recently moved to digital cameras. How has the change affected your photography, and what type of equipment did you typically use for the book?

Paul: We purchased Canon EOS 5Ds not long after they first came out. At first we used the Sigma 50 mm 1:1 lens, but switched to the Sigma 70 mm 1:1 when they became available. Because you never know what you will find on the next dive, we prefer a shorter 1:1 lens for versatility. They provide good depth of field with just a touch of telephoto, which allows us to photograph moderate-sized animals as well as tiny subjects with a single set up. We also believe in keeping things compact and simple. Both of us exclusively use manual focus and exposure and a single strobe. Ned uses an Ikelite housing. I’m currently using a Subal housing. Of course there are many positive aspects of digital vs. film, but probably the most important for us is no longer running out of film!

What were the most challenging animals to photograph?

Ned: For me, it was without question, coral commensal shrimp that live deep within the branches of Acropora coral. We began calling them 30-minute shrimp, because that’s the average time it took Liberty and me to get an acceptable photograph. These little shrimp, which belong to several genera, are not terribly difficult to find, but coaxing them into the open for an image was another matter. Liberty used a pair of satay sticks like a surgeon, patiently attempting to maneuver his reluctant subject into a position where the strobe could penetrate. When one finally popped into position, it was for a second at best. All the while, I was constantly shifting position and focusing like mad. Liberty would get fixated on an especially tough customer and refused to give up even if the effort took an entire dive. But what a celebration, when we finally got the shot.

Paul: I’ve just got to inject a little humor here. Anyone who has worked with wildlife knows that there are many animals that are extremely difficult to approach for a good photograph. Try as you might, they will swim away or dart into a hole before you can ease into position. Even though it is terribly frustrating, in our business we need to get shots of every animal no matter how elusive. Well, if there is one thing we’ve learned, it’s to keep trying. Every time you see an extremely wary animal, give it a try. If it immediately bolts, forget it and move on. Eventually, a dozen or a hundred attempts later, quite unexpectedly you are able to move in and get your shot. Why? Usually we never know, so we simply chalk it up to finding a “dumb one”. Over the years, we’ve enjoyed joking about the dumb ones, but actually we’ve come to believe there is a certain ring of truth to the idea.

Reef Creature Identification:Tropical Pacific is now available as signed and numbered pre-release editions. Books numbered 1-5 are up for auction with the proceeds going to the charity REEF, and books 6-500 are available to purchase. Both special editions will have a seal attached denoting their special status, and increasing their value as collectors items.